|

Population-based vs individual need practise

General Definitions

Population-based practise:

"It always begins with identifying everyone who is in the population-of-interest or the population-at-risk."

"While Public Health tends to focus on the public at large, population health pays greater attention

to more narrowly-defined communities."

"Population-based practise reflects the priorities of the community...."

The NZ Ministry of Health (MoH) Health Service User population (HSU) is based on population criteria such as

PHO enrolment and ethnicity - see HSU -and is used to define a population denominator.

Individual-based practise:

The needs of the person/patient are explored and managed independent of population-based criteria such as

race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion etc.

"Benefits of needs-based care ... [it] improves health outcomes, reduces inequalities [and]

focuses on quality rather than quantity."

Reasons we disagree with population-based health in General Practice:

Population-based policies have (until recently) been preferred by public health and political decision makers

because it appears to aim often limited resources to where the maximum need is but it not only misses those

with a need not in the defined population but it wastes money and resources on those in the defined population

without the need. Counter-intuitively, this often results in worse health statistics as we have seen occurring

in the last 20 years after the introduction of the Primary Health Care Strategy specifically set up in 2001 to

be population-based.

My concerns about this approach are multiple and include:

- Patient resistance to being labelled, stereotyped and thus profiled. Most of my patients of all races want to

be known as "Kiwi" or "New Zealander" without reference to their race, ethnicity, religion, and many strongly

object to any ethnicity or religious "required field" on computer forms to the extent that some are prepared to

lie, (like claiming to be a druid or Jedi or Atlantian!!) or to sabotage results by telling the pedantic truth

such as correctly claiming to be a Pacific Islander despite having European or Asian ancestors because they were

born in a Pacific island called North Island (of New Zealand)!;

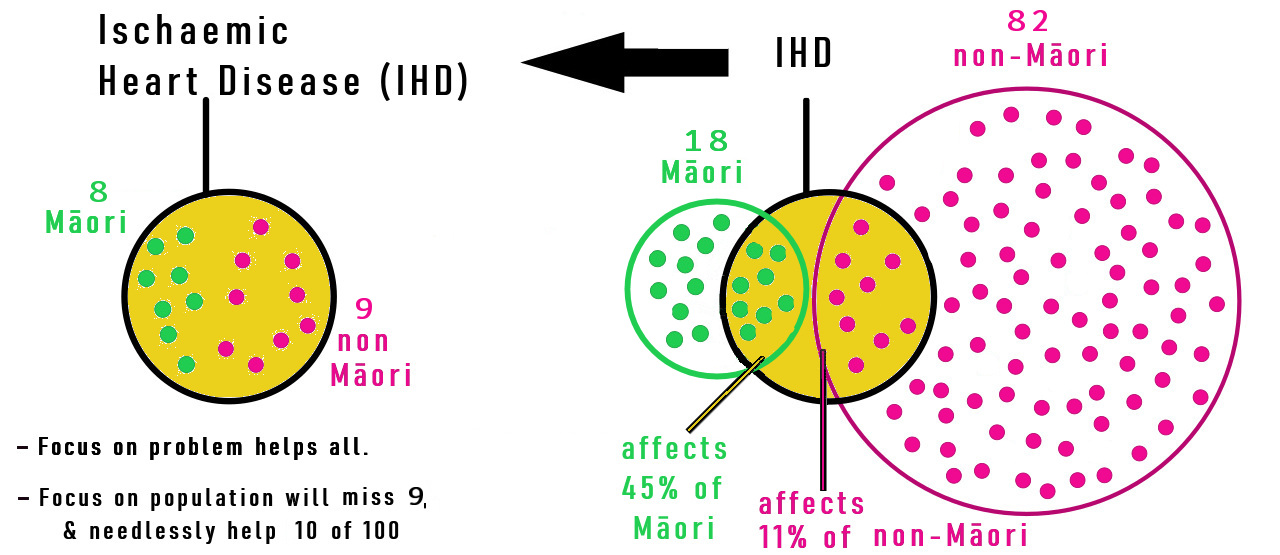

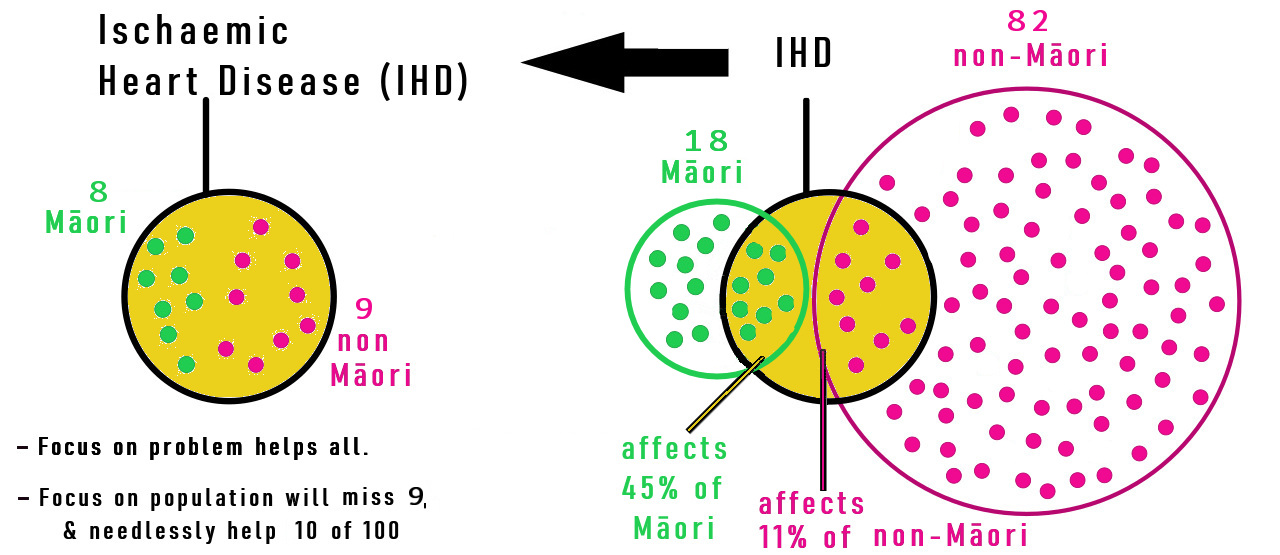

- Many population-based policies fall into the Relative Risk Fallacy by not understanding the statistical

concepts of RELATIVE vs ABSOLUTE. Just because a certain minority group has a higher relative risk,

it doesn't mean they have a higher absolute risk within the whole population. As such, need-based policies

which aim prevention and treatment at the problem, are often cheaper and more equitable than population-based

policies focusing on the group with a higher relative risk.

This is also known as the Base Rate Fallacy described below.

|

| Figure 1: An example of a high Relative Risk (45% compared to 11%) driving costly and ineffective health policy.

|

Having said that, a needs-based system still needs to address barriers to prevention and treatment that a

higher risk group has;

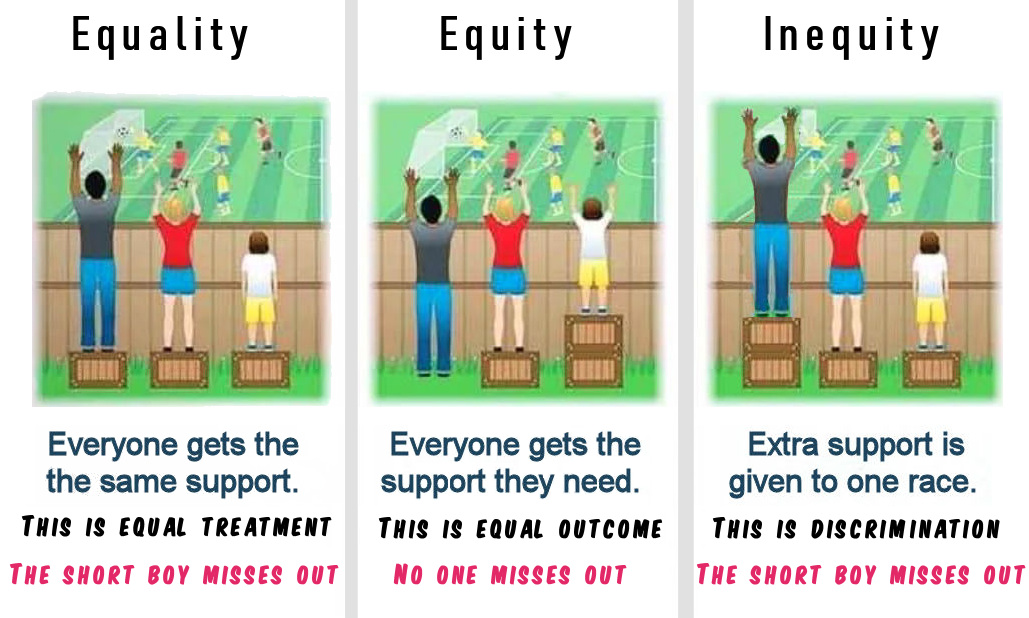

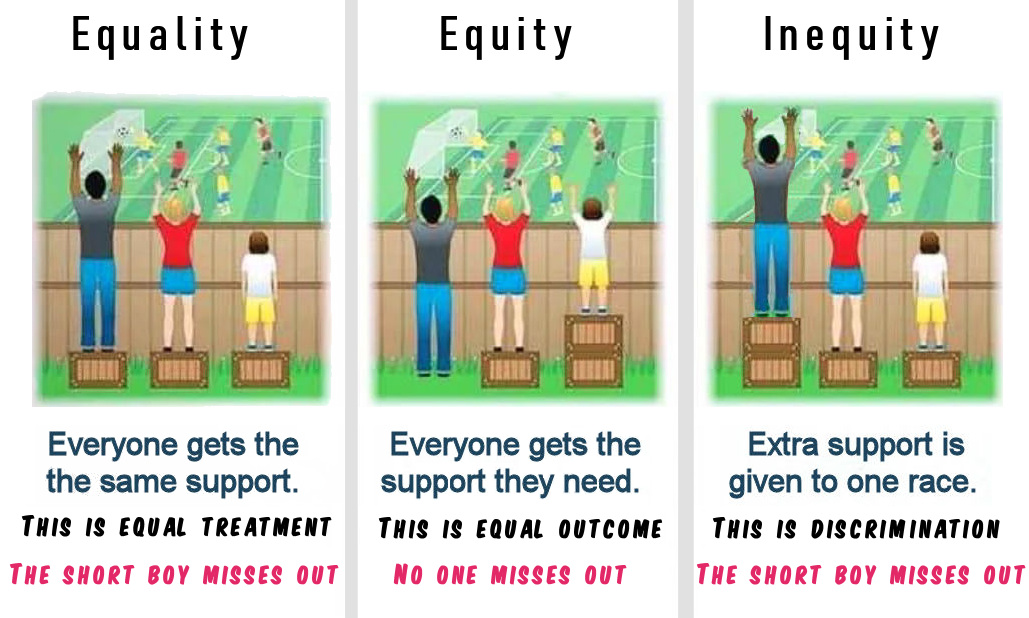

- Restricting a prevention or treatment to one or more groups is discriminatory and stereotyping

(as well as cost inefficient);

- If someone isn't in a particular ethnic, gender or deprivation group they may miss out on screening,

prevention and even early treatment, creating further inequity;

|

| Figure 2: Here, equal outcome (equity) comes from addressing the need (shortness), not population type or equal help.

|

- Defining people by ethnicity has other concerns:

- Many people have more than one ethnicity but are forced to be labeled by one

(often the one that provides some benefit);

- There is confusion by both patients and policy makers between Race (biologic makeup) and

Ethnicity (cultural identity);

- Sometimes, biological race affects a disease risk, but more often, risk may relate to factors

that may be more common in a particular ethnicity. The risk therefore relates more to correlated

factors, including environment (eg housing, particularly overcrowding), lifestyle (eg diet,

smoking and exercise), as well as poverty. Therefore race, while correlated with these factors,

may not be the causation, so focusing on race may miss the actual modifiable determinants;

- New Zealand research has frequently identified race as a risk factor in many conditions but

by and large has ignored or not researched the reasons for this correlation and how they can be

modified in culturally appropriate ways.

- Preconception, ignorance, and bias will lead to discrimination, but not just for "traditionally

discriminated against" groups. For instance, it is not well known that the group with the highest

suicide rate and lowest life expectancy (6 years lower worldwide) is older MEN?! It would be

unlikely that those advocating population-based discrimination in New Zealand would accept

prioritising men over women in health funding, despite this being an "absolute" greater risk!

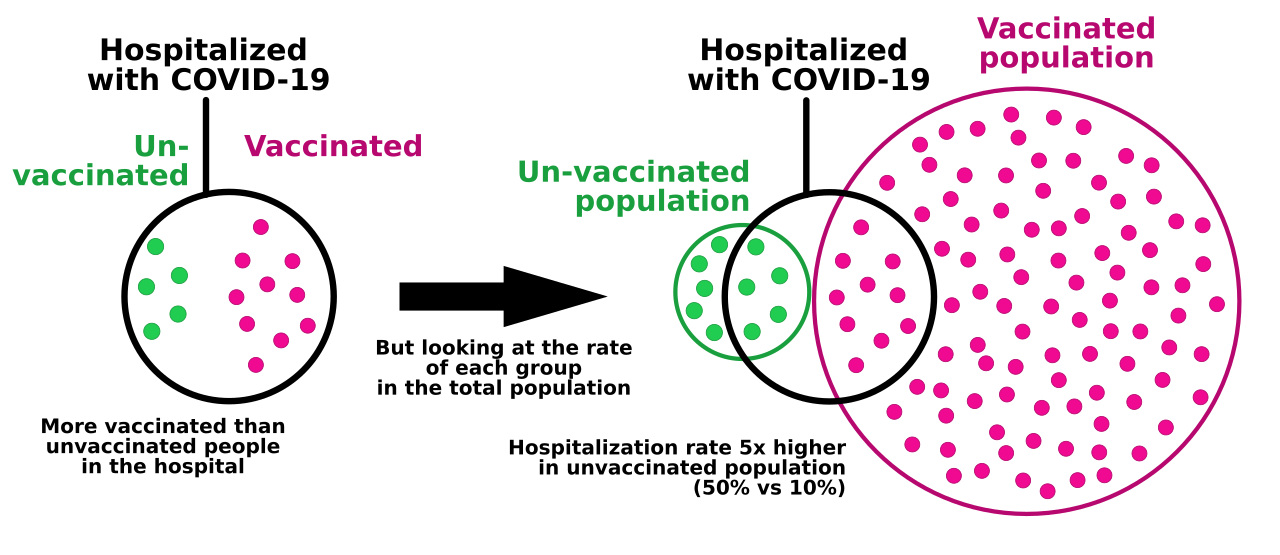

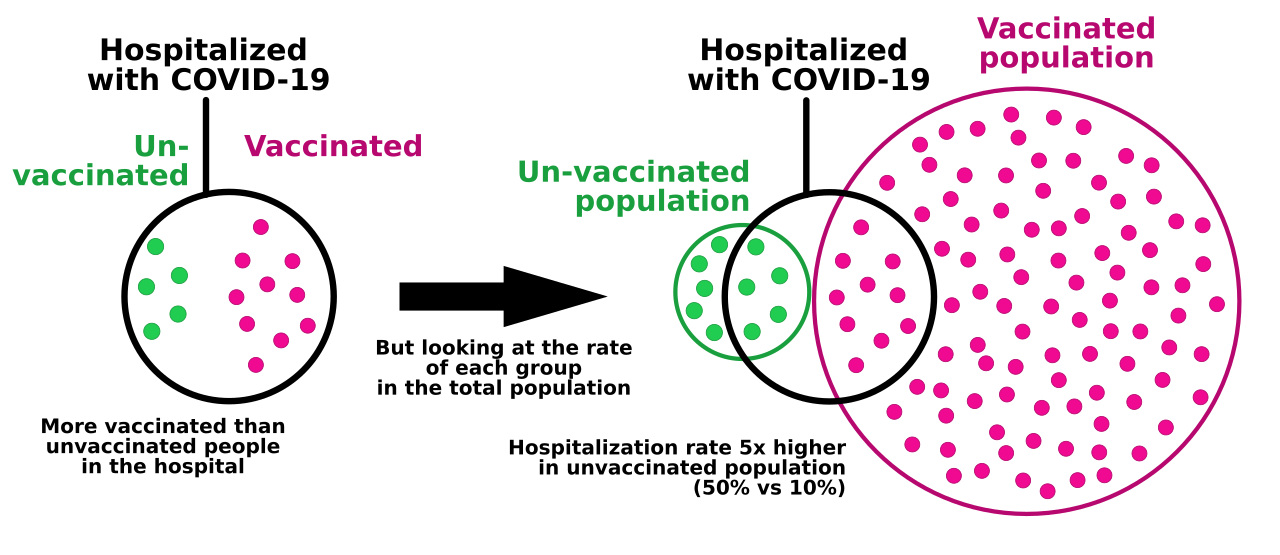

- The Base Rate Fallacy or Base Rate Bias, is a type of fallacy in which people tend to ignore the base

rate (e.g. general prevalence) [1]. It has been used recently to incorrectly claim ineffectiveness of

COVID-19 vaccination (see fig 3) but can also be an example of the Relative Risk Fallacy mentioned above.

|

| Figure 3: An example of the Base Rate Fallacy.

|

- If the NZ Ministry of Health (MoH) and Health NZ (Te Whatu Ora) use Health Service User Populations based

on PHO enrolment, the over 400,000 New Zealanders not enrolled in a PHO get ignored despite being a high

risk group.

Actual poorer health experience in this group is at least partially the result of this discrimination.

Cardiovascular risk assessment - Population-based vs actual individual risk

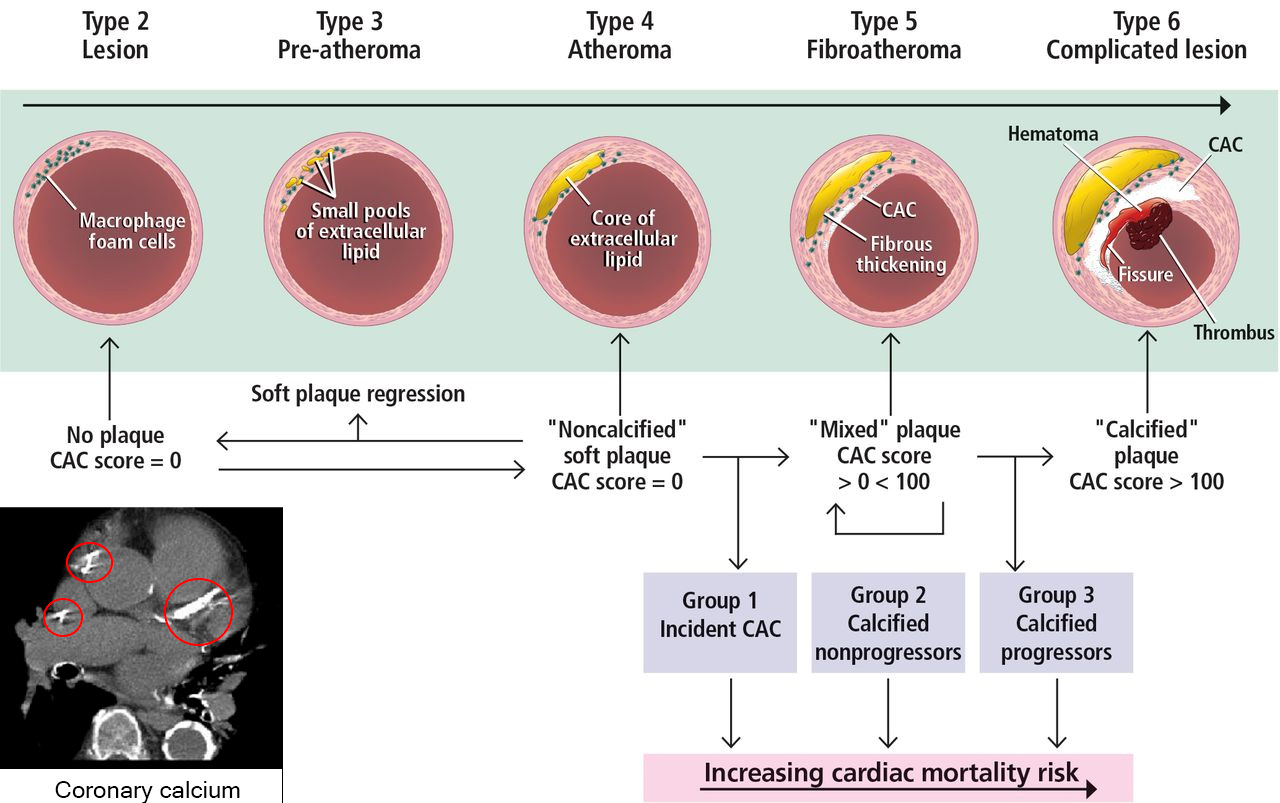

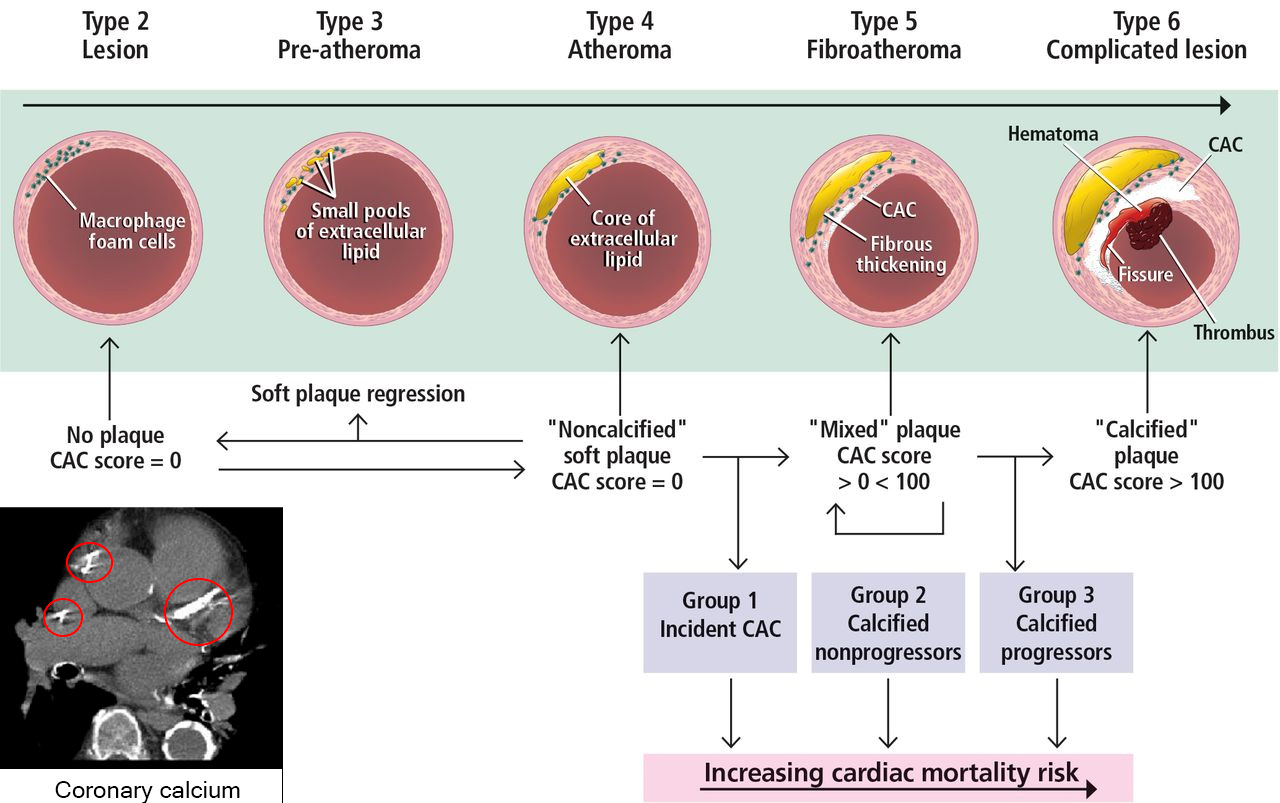

A good example of where population-based screening to determine risk (and thus management) commonly used in NZ is

failing many people is cardiovascular risk screening using a Framingham-type Risk Score or the "PREDICT" Score used in PHO based General

Practice to determine who should receive treatments like statins. It uses age, ethnicity, a diabetic test, smoking history, Blood Pressure and cholesterol profile to predict the 5-year risk.

However, we now have far more accurate individual arterial imaging (Calcium score ± CT angiography) available (but not publicly funded). This is a non-invasive way to identify and grade subclinical (asymptomatic) cardiac atherosclerosis (Coronary Artery Disease) that is present in the coronary arteries instead of just estimating the population-based potential risk. Extensive scientific literature supports the much higher predictive value of the Calcium Score (predicting all coronary events and all-cause mortality) and recommends basing treatment and prevention on the identified disease shown, rather than on the population and risk factor prediction. [2] [3] [4] [5]

This is clearly better than waiting for a coronary syndrome or event to motivate "Secondary" prevention, which is much tighter than primary prevention based on risk factors.

|

| Figure 4: CT Calcium Scoring |

|

References:

- "Logical Fallacy: The Base Rate Fallacy". Retrieved 17-Sept 2024. Fallacyfiles.org/baserate.html

- Aroney C. "Should coronary calcium scoring be used as the central tool for cardiac risk assessment?"

Heart Lung Circ 2019: 28(2); 207-12 Abstract and link to article

- Alexander Chua, Ron Blankstein and Brian Ko "Coronary artery calcium in primary prevention" AJGP (Australian Journal of General Practice) Vol 49, Issue 8, Aug 2020

Link to article; doi: 10.31128/AJGP-03-20-5277

- Mitchell JD, Paisley R, Moon P, Novak E, Villines TC. Coronary artery calcium and long-term risk of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke: The Walter Reed cohort study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2018;11(12):1799–806. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.09.003. PubMed

- Budoff MJ, Shaw LJ, Liu ST, et al. Long-term prognosis associated with coronary calcification: Observations from a registry of 25,253 patients.

J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49(18):1860–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.079. PubMed

|